When Adoption Becomes Inevitable

How lasers inform AI timelines

I didn’t get rich inventing Ethernet. I got rich selling it!

-Bob Metcalfe

Models are moving faster than customers can change.

Some expect AI to fully transform the global economy in a matter of months. The technology is here. The narrative is here. Massive capex is being allocated throughout the stack. Yet, much of the real world will take a decade—or more—to meaningfully integrate AI.

Why?

Invention and diffusion are separate processes. Diffusion only happens after performance and economics clear a bar and when pressure to change exceeds friction.

Lasers & Inertia

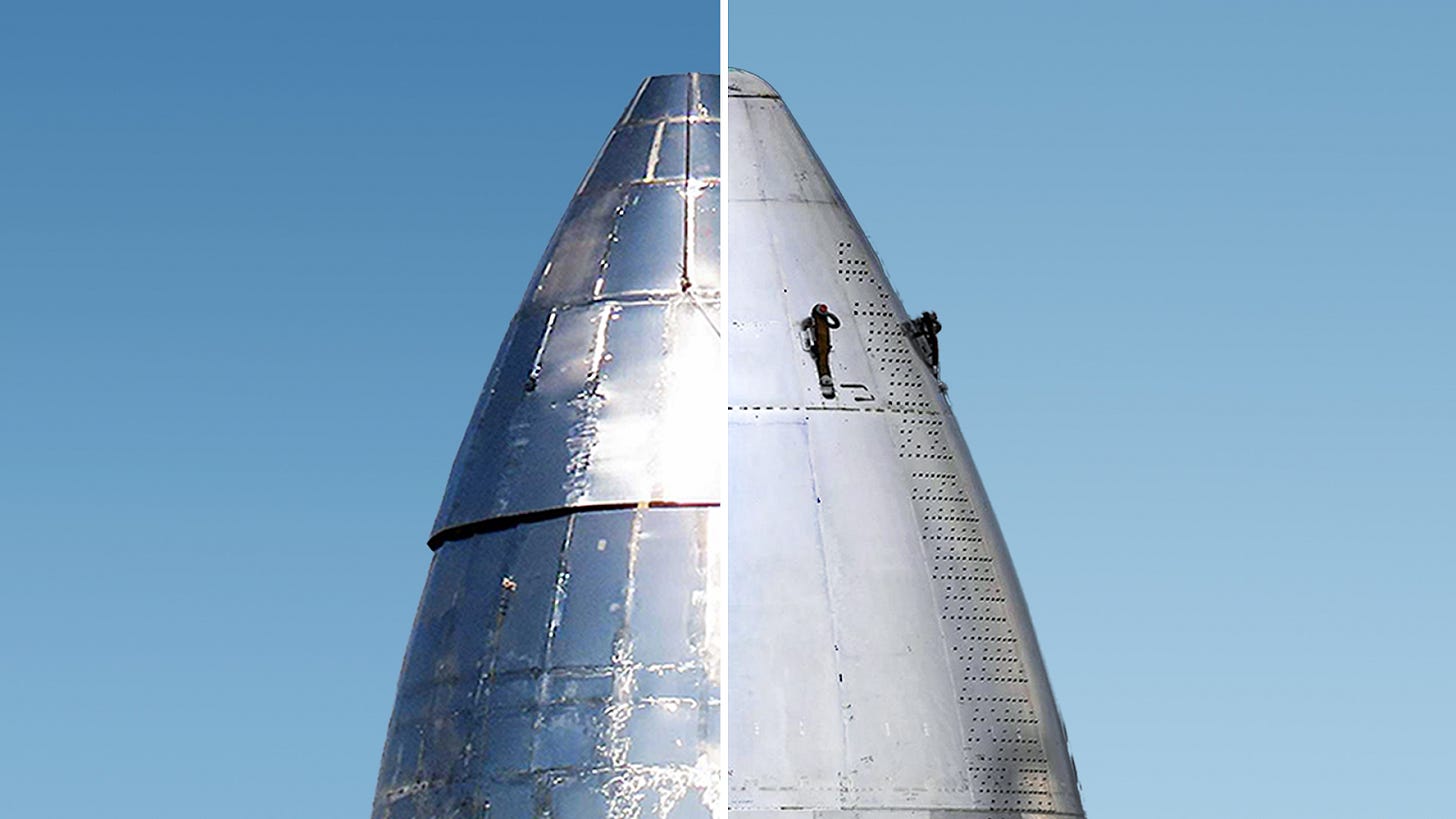

A little while back, I stumbled across the story of how handheld laser welding came to SpaceX, as told by a former welding engineer.

The company had long used automated laser welding, but many use cases still relied on traditional handheld welding (e.g. small welds, welds on or inside large structures, in-place repairs).

One day, Elon saw a Chinese handheld laser on Twitter and bought one on Amazon. It sat unused. Even when a major equipment vendor released a handheld laser, SpaceX bought one and it still gathered dust.

Eventually one welding process had a high rejection rate. They tried it with the handheld laser and it worked perfectly, but it still wasn’t generalizable for longer welds until a key advancement arrived: automated wire feeding. Now, handheld laser welding was suitable for many more processes.

At this point, it’s tempting to assume adoption is assured because the tech works and the math mathed.

Yet, adoption stalled. The welding engineer had working prototypes and begged other teams to adopt them, but “everybody was too apprehensive to use it in production”.

Then one part’s weld was so difficult that only a single person at the company could complete it, creating massive backlog risk (a career-limiting move in Elon companies). Handheld laser welding, performed by a broader team, was the only plausible way to hit deadlines. The team tried the new process and successfully built their first production work cell.

Even then, the organization still wasn’t on board. The engineer continued his begging campaign to no avail. Nobody wanted to be the person whose new process caused a vehicle failure—even if that process was objectively superior on many metrics.

One day, Elon walked the line, looked at the welds and reportedly said, “This looks like garbage”.

Immediately, perceived risk shifted from “What if this new process fails?” to “Elon will totally fire me if I don’t fix these ugly welds.”

Suddenly, the welding engineer had a line out the door of teams ready to adopt the process: “Please. Let’s do this. Right now.”

Even though deploying handheld laser welding required upstream changes (including updates to design engineering assumptions), urgency overcame inertia. A number of bespoke laser-welding processes made it to production.

The results were better than anyone expected. Compared to prior processes, handheld laser welding reportedly reduced distortion by a factor of 10 and increased throughput by 5-6x.

Demand kept growing, so the welding engineer created a chart of pre-qualified procedures so he didn’t have to be involved with each new use case. Within a month, it exploded and they lost track of how many procedures were in production.

Handheld laser welding had won over traditional welding techniques.

Throughout all of this, notice that sufficient laser welding technology was merely the start of the battle. The larger blockers were a superposition of individual career risk and organizational inertia, only overcome with overwhelming external pressure.

Good market timing requires the combination of economically viable technology and where pressure overcomes organizational friction.

Trader vs Maker Market Timing

When people refer to “market timing,” they often conflate two different things:

Trader Market Timing: whether it’s the right time to buy or sell an asset.

Maker Market Timing: whether a specific customer set actually adopts a product.

Trader Market Timing matters for revenue multiples, but Maker Market Timing determines whether there’s any revenue at all.

Diffusion

Four factors control when customers actually buy products:

Performance: Does it work in the real world? Is it reliable enough across edge cases? Can it be operationalized at scale?

Economics: Is it viable when you incorporate all costs: compute, integration, compliance, training, and ongoing maintenance?

Friction: How hard is it to discover, decide, and deploy? Is it complex to communicate? Easy to try? Easy to implement at scale? Are results measurable and attributable?

Pressure: What causes urgent effort for or against change? Are there economic, regulatory, competitive or political forces pushing urgency? Will people lose their jobs if the product replaces labor? What’s the balance of career upside vs downside amongst decision makers?

Diffusion happens when net pressure overcomes friction, but only after performance and economics are viable.

Friction vs Pressure

Performance and Economics are relatively legible. Failures are easy to diagnose.

Friction and Pressure are illegible and can nuke even sophisticated teams. Determining whether a complex group of humans will actually alter their workflow to adopt the product requires deep industry context and more than a little wisdom.

Most AI “slow adoption” stories today are SpaceX handheld lasers. Model performance and price issues are easy to see, but products fail through some combination of Friction and Pressure (the latter often in the form of active resistance).

Asking ChatGPT to plan a trip is low-risk, reversible, and lives outside systems of record. Adoption is instant.

Automating health insurance claims adjudication touches payments, compliance, appeal rights, edge cases, and liability. It requires deep integration into brittle workflows and threatens roles in the existing claims ops team. Adoption is a slog.

Founders often assume that access to intelligence is sufficient. It is not. Simply granting an LLM access to a database does not fix a poorly documented workflow that intersects with three different compliance departments.

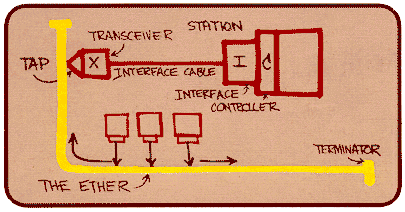

Ethernet and PCs

Consider 3Com, a company founded in 1979 to commercialize Ethernet. They began by building networking hardware for large UNIX systems. The technology worked but the business was meh.

In 1981, the launch of the IBM PC changed everything. Suddenly, millions of identical computers could share expensive peripherals (e.g. laser printers) rather than requiring separate equipment per computer. ROI was obvious. 3Com effectively “bet the company” on this new segment and rode the wave for years.

Metcalfe didn’t get rich because Ethernet suddenly got better in 1981. He got rich by paying attention to an increase in Pressure (strong motivation to avoid buying too many peripherals) paired with low Friction (low switching costs on a new platform) that made Ethernet obvious to a particular set of customers.

Maker Market Timing in AI

We are entering a period where AI model capabilities will outpace organizational absorption. Inevitably, there will be failures.

Blanket pessimism is a lazy coping strategy. Successful founders and investors will distinguish between “wrong tech” and “wrong time”:

Wrong tech: pilots fail on usability/accuracy/latency/reliability/unit economics even with friendly customers.

Wrong time: top of the funnel is slow, procurement stalls, integration stalls, users resist, renewals fail, and incentives misalign.

Startup success won’t come from watching model progress alone. It will come from identifying which handheld lasers are gathering dust, and what specific catalysts create extreme market pull that forces the organization to pick them up.